Researching Across the Spectrum of Autism: Faculty Are Investigating New Strategies, Interventions and Causes

By Theresa E. Ross '80

Napolitano and Nicole Caltabellotta, an undergraduate psychology major, are assisting Amy Learmonth, associate professor of psychology at William Paterson, in her research study, Can Videos Speak the Language of Autism?

Learmonth is one of several William Paterson University faculty members across various disciplines conducting research related to autism spectrum disorders. New Jersey has the highest reported rate of autism in the nation—one in 45 children in the state are diagnosed with the developmental disability, according to the latest reports from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nationally, autism rates have jumped 30 percent since 2012. One in nearly every 68 children is estimated to have this disorder.

Learmonth received a $126,000 grant from New Jersey for her two-year project. The grant is among $2.5 million awarded to six institutions in 2014 by the Governor’s Council for Medical Research and Treatment of Autism. “We’re investigating whether children with autism will learn better from a video or a live person,” explains Learmonth, a developmental psychologist. In her study, children are shown how to complete a puzzle by either a live demonstrator on a magnet board or by a video demonstration.

Learmonth received a $126,000 grant from New Jersey for her two-year project. The grant is among $2.5 million awarded to six institutions in 2014 by the Governor’s Council for Medical Research and Treatment of Autism. “We’re investigating whether children with autism will learn better from a video or a live person,” explains Learmonth, a developmental psychologist. In her study, children are shown how to complete a puzzle by either a live demonstrator on a magnet board or by a video demonstration.

Photo at right: Amy Learmonth, associate professor of psychology, with graduate student Jessica Napolitano

“We know that typically developing children learn by imitating the people around them,” Learmonth explains. Her pilot study will determine whether children with autism have a different mode of imitating. One hypothesis is that video instruction may work better because it takes away much of the social stimuli that children with autism have difficulty processing. By removing the stimuli of a live instructor, they may be better able to focus on learning the task.

“And more importantly,” says Learmonth, “when these children learn things from a touchscreen video or a person, can they transfer that knowledge to the real world? We are hoping that this research will determine the means of teaching some adaptive skill that they can use in their lives.”

Learmonth anticipates that her pilot study will lead to a larger study where she will collaborate with other researchers. “This will allow for a closer examination of the skills of this population and a greater understanding of the mechanisms of imitation,” she says.

Therapeutic interventions for children with autism—the tools and strategies being used in the classroom—are ahead of science, says Learmonth. “In the classroom, teachers are trying different methods to help children with autism spectrum disorders and going with what works, but science needs to catch up,” she says.

Giving teachers strategies to use in the classroom

In the University’s College of Education, students are learning a whole range of strategies that may help children with autism.

Photo at left: Special education and counseling faculty members Manina Urgolo Huckvale and Irene Van Riper

Photo at left: Special education and counseling faculty members Manina Urgolo Huckvale and Irene Van Riper

William Paterson now offers a master’s degree in special education with a concentration in autism spectrum disorders and other severe disabilities. The program is the only one of its type in the state specifically designed to help teachers working with students on the autism spectrum who have significant intellectual disabilities.

“We developed this track because of the needs of teachers,” says Manina Urgolo Huckvale, associate professor and chair in the University’s Department of Special Education and Counseling. The program, which began in fall 2014, guides teachers in designing and conducting action projects that can be put to immediate use in their classrooms.

“Many teachers are working in private schools with students who have severe disabilities concurrent with autism,” explains Urgolo Huckvale. “They are teaching children who have severe communication deficits or are developmentally delayed. And they are looking for help.”

“While a lot of programs in the state concentrate specifically on using applied behavioral analysis (ABA), it may not work for every student—or work for a long time,” says Urgolo Huckvale. “So we’ve decided to bring in other therapies as well as part of this new master’s degree concentration.”

For example, one of the evidence-based interventions being taught is Discrete Trial Training (DTT), developed in 1987. This intervention focuses on managing a child’s learning opportunities by teaching a specific, manageable task until mastery. In children ages two to six, it has been shown to increase levels of cognitive skills, language skills, adaptive skills, and compliance skills. Another intervention is Social Stories™, developed in 1993 by Carol Gray, which uses stories written by the student and the teacher in a vocabulary that the student understands. Such stories have been shown to increase levels of pro-social behaviors in ages two to 12.

“A teacher in our program will learn all the strategies and curricula available to support the teaching of students with autism spectrum disorder and severe disabilities,” says Irene Van Riper, assistant professor, special education and counseling.

Van Riper gives her graduate students the pros and cons of all the interventions available so that they may choose what will work in each situation. “I had a couple of graduate students (teachers) who were using ABA and were surprised that there are other treatments that work beautifully—and they can use them concurrently with ABA or separately,” she notes.

“One assignment I recently gave graduate students was to write a ‘social story’ for a child in their class. Each teacher came back to say that the reading of the social story was extremely beneficial for their student. They were able to experience the results first-hand,” she says.

In addition to trying various evidence-based interventions, this master’s degree program also stresses collaboration with other professionals, the parents, and the family. “It is very important to build a bridge with them,” says Van Riper. “Our program focuses on how to be collaborative and build those bridges.

Urgolo Huckvale and Van Riper are also co-authoring a “how to” book for teachers of children with autism and severe disabilities (Roman & Littlefield Publishing). The book will focus on evidence-based strategies that are being taught to graduate students as part of William Paterson’s master’s degree program, and each chapter will be written by a faculty member in the College of Education.

“One of the purposes of our master’s degree concentration in autism is to give teachers the tools necessary to handle every situation that they may encounter, be it behavior, social skills, or academic. It is essential for them to be prepared to use the strategies needed at any given moment,” says Van Riper.

Which picture works best when teaching children with autism?

Children with autism experience difficulty with communication, sensory integration, and social skills, although visual-spatial skills are a relative strength for them. Therefore, treatment techniques often use visual supports such as pictures. Faculty in the Department of Communication Disorders and Sciences are researching what information contained in a picture is most helpful to children with autism.

When Johnny needs to go to the restroom, he brings a picture of a potty to his teacher. This is often the way a non-verbal child with autism will communicate, explains Nicole Magaldi, assistant professor of communication disorders and sciences.

“Visual supports are a huge part of working with children with autism. Yet, we don’t really know if there’s something in those pictures that could make them more or less helpful,” she says.

Magaldi’s background includes more than 10 years of clinical experience as a speech language pathologist working with children with autism. In 2006, she developed the graduate course Autism Spectrum Disorder, a popular elective that she teaches every other year. The course is popular, she says, because so many graduates end up working with children with autism and are looking for information.

Magaldi, along with Betty Kollia, associate professor of communication disorders and sciences, are researching the use of picture identification in children with autism. In their study, children with autism are given the task to match an object to a picture. The children have three options: a black and white line drawing, a square color photograph, and a color photograph cut in the shape of the object it represents, called TOBIs (true object based icons) by the researchers.

“One of the questions we had is, is more information in the visual picture better, or is less information better?” Magaldi explains. “You would think, for the average child, having an actual picture of an apple cut into the shape of an apple is better because it has the shape, color, and appearance of the object it represents. Or for some, maybe less is better—just a black and white drawing with nothing distracting. I think there’s a theoretical argument for either,” she adds.

Kollia and Magaldi have collaborated on other studies concerning autism. Their current study grew out of similar research that Kollia conducted with graduate student Mary Deimer in 2004.

“Research is desperately needed to understand the most effective ways of working with autism,” says Kollia. “This study will provide us with information about picture recognition. Children respond differently to the various types of visual supports. If we can optimize at least one aspect of this communication, then we can maximize a child’s engagement in activities.”

Can omega-3 fatty acids help prevent autism spectrum disorder?

While educators, speech pathologists, developmental psychologists, and other faculty are exploring ways to help children already diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders, other faculty are looking for ways to prevent it.

Robert Benno, professor of biology, is doing research with mice to determine if a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids can prevent autism. Preliminary results are already supporting his hypothesis that omega-3 fatty acids, which are anti-inflammatory, can protect against autistic-like phenotypes.

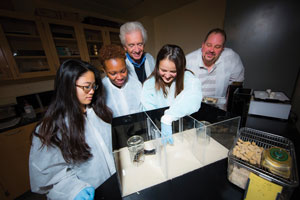

Photo at left: Robert Benno, professor of biology (center), in the lab with students (left to right) Rebecca Atencio, Maya McDougal, and Erin Connor, and Norman Schanz, principal lab technician

Photo at left: Robert Benno, professor of biology (center), in the lab with students (left to right) Rebecca Atencio, Maya McDougal, and Erin Connor, and Norman Schanz, principal lab technician

In Benno’s study, female mice are randomly assigned to two groups: one receiving a diet high in DHA (omega-3) and one low in DHA. At approximately 60 days of age, when they have high levels of omega-3 in their brains, the experimental animals are mated. One group is injected with a viral mimic that produces autism-like behaviors and the second group, the control group, receives a saline injection. Their offspring are being studied for changes in developmental behaviors or social behaviors that may be similar to those experienced in the “autistic-like” mouse.

How can a mouse be “autistic like”? The mice are injected with a viral mimic that has been shown to model the three core symptoms of autism: impaired social communication, poor social interaction, and repetitive behaviors like habitual self-grooming. In the autism-like group, early results are already showing that omega-3 lessens the inflammatory response, says Benno.

For the past 25 years, Benno has conducted research in the field of developmental behavior genetics. He recently became interested in applying his research expertise to probe the underlying causes of autism and the development of treatments based on an understanding of this abnormal process.

Benno has performed studies related to autism spectrum disorders with several of his colleagues in biology. In collaboration with Emmanuel Onaivi, professor of biology and a neuropharmacologist, they demonstrated neurochemical differences in the brains of autistic-like mice relative to controls. They showed that these chemical differences translate into some of the behavioral differences that predominate in this strain. A paper published in Current Neuropharmacology highlights the results of their collaboration.

Benno and Jeung Woon Lee, associate professor of biology, found that an autistic-like mouse strain exhibits a decreased response to painful stimuli, a finding that is consistent with that observed in humans diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. And most recently, Benno and Kendall Martin, associate professor of biology and a microbial ecologist, have investigated gut bacteria in the autistic-like mouse model and whether probiotics can reverse behavioral abnormalities.

Benno theorizes that the increase in autism syndrome disorders in humans could be due to a number of things, including environmental toxins and an altered diet, which no longer protects people from viruses. That’s where his interest in DHA originated.

“Researchers are beginning to look at inflammatory processes in terms of many diseases, including Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, and what seems to be causing all of this,” says Benno. The common thread, he speculates, may be viral insults during early brain development. “I doubt that there are more viruses out there in the world—they do mutate—but I think our ability to deal with these viruses is decreasing.”

“I am very excited by the nature of my latest project involving DHA,” says Benno. “I believe that these experiments will have the potential to shed light on the mechanisms and possible treatment for autism spectrum disorders.”